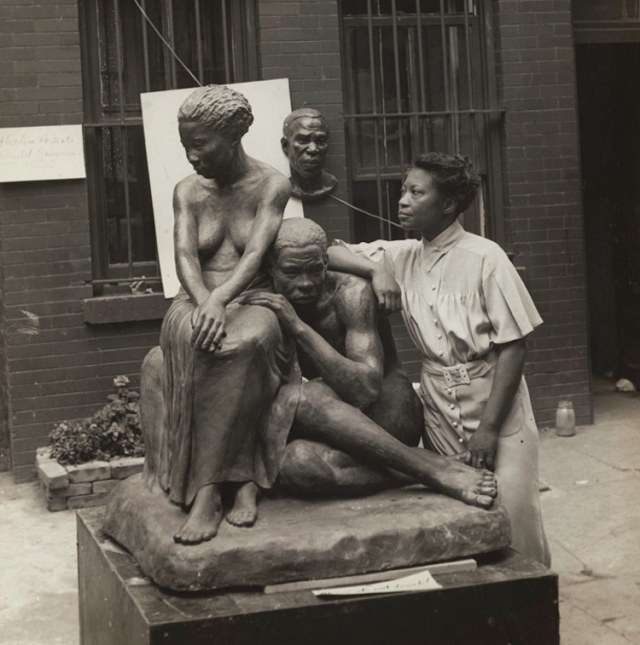

Andrew Herman (active 1930s–1940s), Federal Art Project, Works Progress Administration

Augusta Savage with her sculpture Realization, 1938 (Gelatin silver print, 10 x 8 in.

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, NYPL, Photographs and Prints Division, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations, 86-0036) (Photo: New York Historical Society [Public Domain])

In the early 20th century, a remarkable renaissance emerged in Harlem. On the historic heels of the Great Migration, a mass exodus of over six million African Americans fleeing the segregated South, the New York City neighborhood became a cultural hub for Black creatives. While a wealth of figures formed this “golden age” of art, music, and literature, the contributions of sculptor Augusta Savage can be found at its core.

As a teacher and advocate for African Americans in the arts, Savage shaped the careers of some of the Harlem Renaissance‘s most prominent artists. While she was a skilled ceramicist her in own right, Savage considered the impression she left on her students to be her true masterpiece. “I have created nothing really beautiful, really lasting, but if I can inspire one of these youngsters to develop the talent I know they possess, then my monument will be in their work,” she said

Although this “monument” is at the heart of the Harlem Renaissance, many people are unaware of Savage’s role in the groundbreaking movement. Here, we take a look at her life and work, from her humble beginnings in clay to her mold-breaking legacy.

A Career Takes Shape

Augusta Savage, “Portrait of a Baby,” 1942

(Terracotta, 10 x 8½ x 8 in.

Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY) (Photo: New York Historical Society [Public Domain])

In 1892, Augusta Savage was born in Green Cove Springs, a lush city in Florida named—and known—for its natural landscape. Built around a warm mineral spring, the city is rich in red clay. With this medium conveniently at her disposal, Savage spent her childhood crafting small ceramic animals. While her Methodist minister father disapproved of her hobby, a teenaged Savage taught sculpting in high school—a stint that shaped the foundation for a career in arts education.

In 1919, Savage solidified her role as an innovative sculptor when her work won an award for originality at a Florida fair. Two years later, she moved to New York City, where she applied to the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, a progressive, scholarship-based university in Manhattan. Though up against 142 male applicants, Savage was accepted, and, in 1923, she earned her degree—an entire year early.

Unidentified photographer,

Augusta Savage viewing two of her sculptures, Susie Q and Truckin, c. 1939 (Gelatin silver print, 10 x 8 in.

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, NYPL, Photographs and Prints Division, Art & Artists-Prophet, Nancy-Stull, Henry, 92-0360 Box 6) (Photo: New York Historical Society [Public Domain])

While Savage was rightly recognized for her talents at Cooper Union, her early career experiences were not without racism and sexism. In 1923, a committee rejected her application for a summer art program in France due to her race. Savage contested the decision to no avail. However, committee member and sculptor Hermon Atkins MacNeil championed Savage’s work, eventually becoming her teacher.[…]

Continue reading: How Augusta Savage Helped Shape the Harlem Renaissance