We can pick out a conversation in a loud room, amid the rise and fall of other voices or the hum of an air conditioner. We can spot a set of keys in a sea of clutter, or register a raccoon darting into the path of our onrushing car. Somehow, even with massive amounts of information flooding our senses, we’re able to focus on what’s important and act on it.

Attentional processes are the brain’s way of shining a searchlight on relevant stimuli and filtering out the rest. Neuroscientists want to determine the circuits that aim and power that searchlight. For decades, their studies have revolved around the cortex, the folded structure on the outside of the brain commonly associated with intelligence and higher-order cognition. It’s become clear that activity in the cortex boosts sensory processing to enhance features of interes

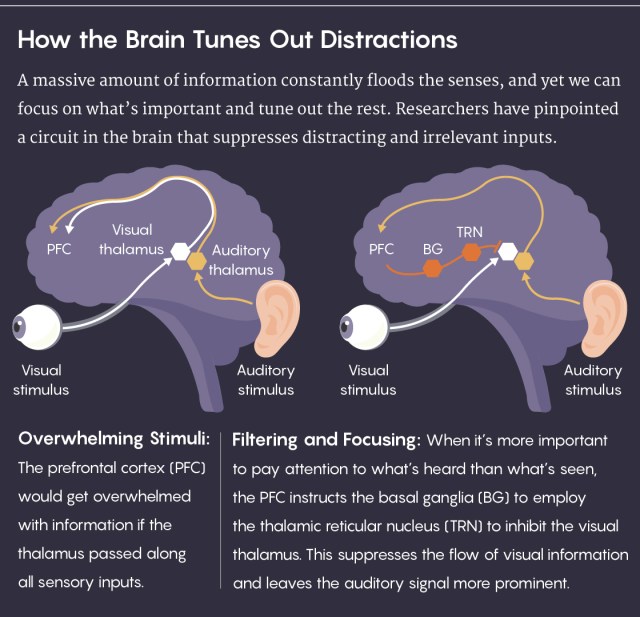

But now, some researchers are trying a different approach, studying how the brain suppresses information rather than how it augments it. Perhaps more importantly, they’ve found that this process involves more ancient regions much deeper in the brain — regions not often considered when it comes to attention.

By doing so, scientists have also inadvertently started to take baby steps toward a better understanding of how body and mind — through automatic sensory experiences, physical movements and higher-level consciousness — are deeply and inextricably intertwined.

Hunting for Circuits

For a long time, because attention seemed so intricately tied up with consciousness and other complex functions, scientists assumed that it was first and foremost a cortical phenomenon. A major departure from that line of thinking came in 1984, when Francis Crick, known for his work on the structure of DNA, proposed that the attentional searchlight was controlled by a region deep in the brain called the thalamus, parts of which receive input from sensory domains and feed information to the cortex. He developed a theory in which the sensory thalamus acted not just as a relay station, but also as a gatekeeper — not just a bridge, but a sieve — staunching some of the flow of data to establish a certain level of focus.

But decades passed, and attempts to identify an actual mechanism proved less than fruitful — not least because of how enormously difficult it is to establish methods for studying attention in lab animals.

That didn’t stop Michael Halassa, a neuroscientist at the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He wanted to determine exactly how sensory inputs got filtered before information reached the cortex, to pin down the precise circuit that Crick’s work implied would be there.

He was drawn to a thin layer of inhibitory neurons called the thalamic reticular nucleus (TRN), which wraps around the rest of the thalamus like a shell. By the time Halassa was a postdoctoral researcher, he had already found a coarse level of gating in that brain area: The TRN seemed to let sensory inputs through when an animal was awake and attentive to something in its environment, but it suppressed them when the animal was asleep.

In 2015, Halassa and his colleagues discovered another, finer level of gating that further implicated the TRN as part of Crick’s long-sought circuit — this time involving how animals select what to focus on when their attention is divided among different senses. In the study, the researchers used mice trained to run as directed by flashing lights and sweeping audio tones. They then simultaneously presented the animals with conflicting commands from the lights and tones, but also cued them about which signal to disregard. The mice’s responses showed how effectively they were focusing their attention. Throughout the task, the researchers used well-established techniques to shut off activity in various brain regions to see what interfered with the animals’ performance.

As expected, the prefrontal cortex, which issues high-level commands to other parts of the brain, was crucial. But the team also observed that if a trial required the mice to attend to vision, turning on neurons in the visual TRN interfered with their performance. And when those neurons were silenced, the mice had more difficulty paying attention to sound. In effect, the network was turning the knobs on inhibitory processes, not excitatory ones, with the TRN inhibiting information that the prefrontal cortex deemed distracting. If the mouse needed to prioritize auditory information, the prefrontal cortex told the visual TRN to increase its activity to suppress the visual thalamus — stripping away irrelevant visual data.

The attentional searchlight metaphor was backward: The brain wasn’t brightening the light on stimuli of interest; it was lowering the lights on everything else.[…]

Continue reading: To Pay Attention, the Brain Uses Filters, Not a Spotlight | Quanta Magazine