Researchers at CU Boulder report that they may have solved a geophysical mystery, pinning down the likely cause of a phenomenon that resembles a wrench in the engine of the planet.

Researchers at CU Boulder report that they may have solved a geophysical mystery, pinning down the likely cause of a phenomenon that resembles a wrench in the engine of the planet.

In a study published today in Nature Geoscience, the team explored the physics of “stagnant slabs.” These geophysical oddities form when huge chunks of Earth’s oceanic plates are forced deep underground at the edges of certain continental plates. The chunks sink down into the planet’s interior for hundreds of miles until they suddenly—and for reasons scientists can’t explain—stop like a stalled car.

CU Boulder’s Wei Mao and Shijie Zhong, however, may have found the reason for that halt. Using computer simulations, the researchers examined a series of stagnant slabs in the Pacific Ocean near Japan and the Philippines. They discovered that these cold rocks seem to be sliding on a thin layer of weak material lying at the boundary of the planet’s upper and lower mantle—roughly 660 kilometers, or 410 miles, below the surface.

And the stoppage is likely temporary: “Although we see these slabs stagnate, they are a fairly recent phenomena, probably happening in the last 20 million years,” said Zhong, a co-author of the new study and a professor in CU Boulder’s Department of Physics.

Going stagnant

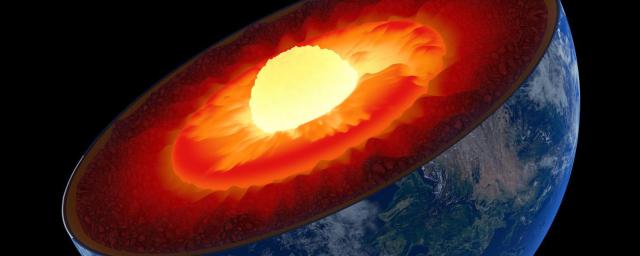

The findings matter for tectonics and volcanism on the Earth’s surface. Zhong explained that the planet’s mantle, which lies above the core, generates vast amounts of heat. To cool the globe down, hotter rocks rise up through the mantle and colder rocks sink.

“You can think of this mantle convection as a big engine that drives all of what we see on Earth’s surface: earthquakes, mountain building, plate tectonics, volcanos and even Earth’s magnetic field,” Zhong said.

The existence of stagnant slabs, which geophysicists first located about a decade ago, however, complicates that metaphor, suggesting that Earth’s engine may grind to a halt in some areas. That, in turn, may change how scientists think diverse features, such as East Asia’s roiling volcanos, form over geologic time […]