By Mir Sabbir

BBC Bengalí, Dhaka

A family in Bangladesh struggles with an extremely rare genetic condition, “immigration delay disease”.

A family in Bangladesh struggles with an extremely rare genetic condition, “immigration delay disease”.

Apu Sarker was showing his open palm to me on a video call from his home in Bangladesh. Nothing seemed unusual at first, but as I looked closer I could see the smooth surfaces of his fingertips.

Apu, who is 22, lives with his family in a village in the northern district of Rajshahi. He was working as a medical assistant until recently. His father and his grandfather were farmers.

The men in Apu’s family appear to share a genetic mutation so rare it is thought to affect only a small handful of families in the world: they have no fingerprints.

Back in the day of Apu’s grandfather, having no fingerprints was no big deal. “I don’t think he ever thought of it as a problem,” Apu said.

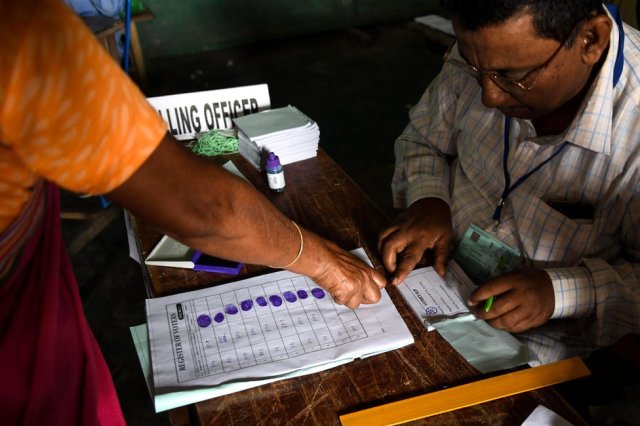

But over the decades, the tiny grooves that swirl around our fingertips – known properly as dermatoglyphs – have become the world’s most collected biometric data. We use them for everything from passing through airports to voting and opening our smartphones.

In 2008, when Apu was still a boy, Bangladesh introduced National ID cards for all adults, and the database required a thumbprint. The baffled employees did not know how to issue a card to Apu’s father, Amal Sarker. Finally, he received a card with “NO FINGERPRINT” stamped on it.

In 2010, fingerprints became mandatory for passports and driver’s licences. After several attempts, Amal was able to obtain a passport by showing a certificate from a medical board. He has never used it though, partly because he fears the problems he may face at the airport. And though riding a motorbike is essential to his farming work, he has never obtained a driving licence. “I paid the fee, passed the exam, but they did not issue a licence because I couldn’t provide fingerprint,” he said.[…]

Continue reading: The family with no fingerprints