Syracuse University’s SUPARS system was developed by Pauline Atherton as an early antecedent of what we might today call ‘search’. Photo courtesy Syracuse University Libraries Special Collections

Syracuse University’s SUPARS system was developed by Pauline Atherton as an early antecedent of what we might today call ‘search’. Photo courtesy Syracuse University Libraries Special Collections

A group of 1970s campus librarians foresaw our world of distributed knowledge and research, and designed search tools for it

Throughout an unusually sunny Fall in 1970, hundreds of students and faculty at Syracuse University sat one at a time before a printing computer terminal (similar to an electric typewriter) connected to an IBM 360 mainframe located across campus in New York state. Almost none of them had ever used a computer before, let alone a computer-based information retrieval system. Their hands trembled as they touched the keyboard; several later reported that they had been afraid of breaking the entire system as they typed.

The participants were performing their first online searches, entering carefully chosen words to find relevant psychology abstracts in a brand-new database. They typed one key term or instruction per line, like ‘Motivation’ in line 1, ‘Esteem’ in line 2, and ‘L1 and L2’ in line 3 in order to search for papers that included both terms. After running the query, the terminal produced a printout indicating how many documents matched each search; users could then narrow down or expand that search before generating a list of article citations. Many users burst into laughter upon seeing the response from a computer so far away.

The IBM 360 mainframe computing system with printing terminal. Courtesy IBM

The IBM 360 mainframe computing system with printing terminal. Courtesy IBM

As part of a telephone survey afterwards, participants were asked to provide two or three words describing the experience. Of the 78 total words provided, 21 were the same adjective: ‘frustrating’. Participants had trouble signing on to the system and experienced unpredictable failures, ‘irrelevant output’ and, most of all, not knowing ‘what words to use in a search’. Yet they also found the system intriguing and exciting (‘fun’, ‘thorough’, ‘I dig computers’), and 94 per cent said they would use SUPARS (the Syracuse University Psychological Abstracts Retrieval Service) again if it were available. Several offered to keep the experiment running past its deadline by asking their departments to contribute funding to the project.

This group of academic guinea pigs, mostly graduate students in education, psychology and librarianship, were part of a radical online search experiment run by the Syracuse University School of Library Science. SUPARS was one of many ambitious information-retrieval studies that took place between the late 1960s and mid-1970s on US university campuses. A number of factors led to the surge in this research. Developments in computer-processing capability for speed and storage had allowed academic databases and catalogues to be digitised and moved online. Computer terminals were newly modular and could be placed around campuses for decentralised access to mainframes. And military and industry funding for computer-based research was more abundant than it had ever been. Given the opportunity, academic librarians took advantage of the chance to explore this expensive new technology. In turn, universities offered unclassified environments for collaborations with corporate technology firms and military groups; SUPARS was sponsored by the Rome Air Development Center, the laboratory arm of the US Air Force.

It’s easy to see why librarians of the 1970s set out to revolutionise search. Work across the academy was expanding to such a degree that, soon, there would not be enough human librarians to support all of it. Yet, to get the information they needed, researchers would face a time-consuming, physically involved process that required librarian intervention. While academic researchers could browse new issues of journals in their field, for a focused search of all that had come before they still had to consult with a reference librarian to look up the correct Library of Congress subject headings within a multivolume manual. Armed with a set of subject headings, the researcher would then search across the library catalogue for books and in citation indexes for journal articles, including subscription databases such as the Science Citation Index as well as hand-built bibliographies created by their university’s subject librarians. Finally, they would physically track down the correct books and bound periodicals that included articles they thought might be relevant – if the volumes happened to be on the library shelves.

It’s no wonder that SUPARS participants found the system compelling, despite its limitations. And given how familiar university librarians were with the challenges of search, it makes sense that the system they designed bypassed subject headings and citation indexes. What’s more surprising is that, of all the online search experiments that took place during this period – including commercially focused search systems like Lockheed’s Dialog, which has since become an enterprise product – SUPARS mimicked contemporary web search more closely than any other, prefiguring several primary features of web-search protocols we rely on more than 50 years later.

SUPARS and other largely forgotten systems were the forerunners of the contemporary search engines we have today. While the popular history of the internet valorises Silicon Valley coders – or, sometimes, the former US vice president Al Gore – many of the original concepts for search emerged from library scientists focused on the accessibility of documents in time and space. Working with research and development funding from the military and industry, their advances can be seen everywhere in the current online information landscape – from general approaches to ingesting and indexing full-text documents, to free-text searching and a sophisticated algorithm utilising previous saved searches of others, a foundational building block for contemporary query expansion and autocomplete. Indeed, these and many other approaches developed by campus pioneers are still used by the multibillion-dollar businesses of web search and commercial library databases from Google to WorldCat today.

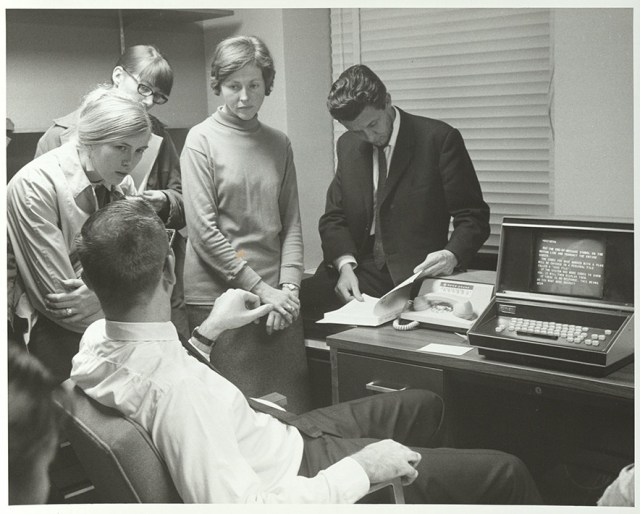

auline Atherton Cochrane (centre) with colleagues working in the Syracuse University Libraries on SUPARS. Photo courtesy Syracuse Libraries Special Collections

auline Atherton Cochrane (centre) with colleagues working in the Syracuse University Libraries on SUPARS. Photo courtesy Syracuse Libraries Special Collections

UPARS was designed by a librarian named Pauline Atherton (who goes by the name of Pauline Atherton Cochrane today). In 1960, aged 30 and early in her library career, she had been the cross-reference editor of that year’s revision of the World Book Encyclopedia, ensuring thorough and accurate cross-linking between different articles. By 1966, she was working at the Syracuse University libraries and in the library school, where in 1968 she demonstrated the first use of an online decimal classification file to aid in search (AUDACIOUS). That same year, she established the first computer-based teaching lab that integrated online search into regular classroom teaching at the library school (LEEP). (In the context of the world before the internet, ‘online’ meant establishing a networked, real-time connection between a mainframe computer and some other remote device, such as a terminal.)

The following year, in 1969, Atherton designed SUPARS with her co-investigator, Jeffrey Katzer, another library science professor at Syracuse. The main goal of the SUPARS project was to provide online searching at a massive scale in order to learn as much as possible about how users searched online, how they felt about it, and what they needed to search better. To do so, the team set up a searchable corpus of scholarly content made available to the entire campus; more than 35,000 recent entries from the American Psychological Association’s Psychological Abstracts. Used for indexing and retrieval in the SUPARS system, this comprised the first database of significant size available online in an unclassified environment. While obviously nowhere near the size and scope of today’s web search, both the user group and the searchable content were enormous for the time.

Two decisions from Atherton and her team made SUPARS truly novel. First, they stripped away all subject headings from the entries in Psychological Abstracts and made all the words directly searchable, except for connectors such as ‘and’ and articles like ‘a’ or ‘the’. This made SUPARS the first system where extensive free text was available online for both searching and output. (They titled their final report ‘Free Text Retrieval Evaluation’.) Second, they saved every SUPARS search in a parallel database that could be queried alongside the abstracts themselves, making SUPARS the first experiment that allowed users to access and use previous searches to find alternative terms or approaches.

[…]

Continue reading: The 1970s librarians who revolutionised the challenge of search | Aeon Essays

is a librarian with a background in academic libraries and scholarly publishing. She works on copyright policy at Google and lectures in the MSc Information Science programme at City, University of London.