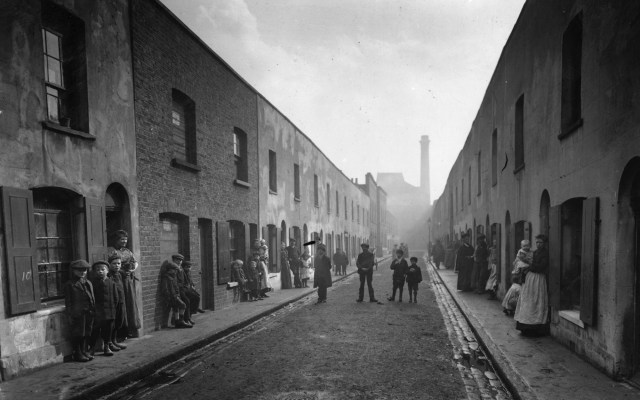

A street in London’s East End in 1912. Topical Press Agency/Getty

A street in London’s East End in 1912. Topical Press Agency/Getty

Slum photography was at the heart of progressive campaigns against urban poverty. And it was a weapon against poor people

A photograph taken in 1880 by Bedford Lemere, a renowned architectural photography firm of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, shows a dimly lit courtyard, narrow and surrounded on three sides by worn brick buildings. Uneven paving stones lead to a passageway, through which, barely visible, a man and a child watch the photographer from a distance, while a spectral presence in the foreground reveals itself to be another person, their form blurred, suggesting they moved during the long exposure time a camera of the era required. The photograph pictures Jerusalem Court in Clerkenwell, London. Most likely, it was commissioned by the Clerkenwell vestry to earmark Jerusalem Court as an area ‘unfit for human habitation’ – a phrase used by housing inspectors to describe dwellings deemed unhealthy for residents to live in. In the annual report for 1899, a special committee, commissioned by the Clerkenwell vestry to examine the condition of courts and blind alleys in the area, states that, according to ‘medical men’, the block of dwellings on the north side of Jerusalem court is ‘very unhealthy, without through ventilation, and such as should never have been built’.

The photograph of Jerusalem Court was, in fact, deliberately taken in such a way as to reinforce the fatal verdict of the ‘medical men’. The emphasis on the enclosed sense of space – enhanced by the camera angle – and the lack of light, dilapidated buildings and stained paving mobilise visual tropes of disease and filth that recur in slum photography to signal urban decay. When presented to the Clerkenwell Sanitary Committee, the photograph read as evidence that the courtyard was a slum area and, as such, an appropriate candidate for clearance and demolition.

Slums have long invited the camera’s gaze. This photograph of Jerusalem Court is characteristic of the many photographs of slum housing taken across Britain since the late 1860s. Most of these are unremarkable in aesthetic terms, but the sheer volume of ‘slum photographs’ held in the archives of British cities such as London, Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham reveals the extent to which slum housing – and, by extension, the management of the working-class populations who lived in it – was a subject of major national concern. From Thomas Annan’s 19th-century photographs of rundown Glasgow tenements, to images of East End slum clearances taken in the 1950s, such images have informed our ideas about how the urban environment might be critically linked to the nation’s social, moral and physical health.

Slums captured the American imagination, too. In the 1880s, Jacob Riis, once a destitute Danish immigrant himself, photographed the abject conditions endured by New Yorkers in the overcrowded tenements of Lower East Side Manhattan. Riis’s photographs revealed for the first time to a suitably scandalised middle-class public how the ‘underclass’ lived, inaugurating a tradition of photographing the most powerless in society, which was built on by 20th-century photographers like Dorothea Lange. While Lange was photographing the rural poor of America’s dust bowl in the 1930s, British photographers like Bill Brandt, Edith Tudor-Hart and Humphrey Spender were documenting British slum life. Brandt made his name showcasing the polarities of class differences in British society. His first book, The English at Home (1936), juxtaposed poverty-stricken working-class neighbourhoods with images of the extravagant homes and lifestyles enjoyed by the British upper classes. Spender began his career photographing daily life in working-class communities for the Mass Observation movement while Tudor-Hart, a radical socialist and Jewish intellectual, photographed deprived areas across London and Wales, focusing on the working lives of women.

Between 1930 and 1950 – when two world wars and extensive bombing compounded the nation’s housing shortage – photographs of slum conditions in British cities taken by Brandt, Tudor-Hart, Spender and others began to feature regularly in the pages of popular photo magazines such as Picture Post, Weekly Illustrated and Lilliput. But did these widely consumed photographs of slum life – teeming in the official records and attracting the eye of documentary photographers – lead to any improvement in the lives of ‘slum dwellers’, forcing local authorities to implement social reform? Or did the visual tropes they promulgated merely reinscribe existing social and political structures that framed working-class people as a powerless group, at best, dependent on the philanthropy of middle-class elites and, at worst, as a filthy ‘underclass’ contaminating Britain’s urban centres? […]

Continue reading: Slum photos were weaponised against the people they depict | Aeon Essays

is a PhD candidate in the School of Journalism, Media and Culture at Cardiff University, Wales. She lives in London.