Want to create a brand new type of protein that might have useful properties? No problem. Just hum a few bars.

Want to create a brand new type of protein that might have useful properties? No problem. Just hum a few bars.

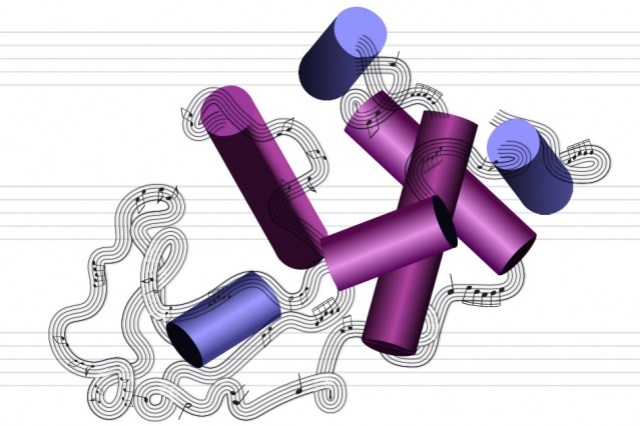

In a surprising marriage of science and art, researchers at MIT have developed a system for converting the molecular structures of proteins, the basic building blocks of all living beings, into audible sound that resembles musical passages. Then, reversing the process, they can introduce some variations into the music and convert it back into new proteins never before seen in nature.

Although it’s not quite as simple as humming a new protein into existence, the new system comes close. It provides a systematic way of translating a protein’s sequence of amino acids into a musical sequence, using the physical properties of the molecules to determine the sounds. Although the sounds are transposed in order to bring them within the audible range for humans, the tones and their relationships are based on the actual vibrational frequencies of each amino acid molecule itself, computed using theories from quantum chemistry.

The system was developed by Markus Buehler, the McAfee Professor of Engineering and head of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at MIT, along with postdoc Chi Hua Yu and two others. As described today in the journal ACS Nano, the system translates the 20 types of amino acids, the building blocks that join together in chains to form all proteins, into a 20-tone scale. Any protein’s long sequence of amino acids then becomes a sequence of notes.

While such a scale sounds unfamiliar to people accustomed to Western musical traditions, listeners can readily recognize the relationships and differences after familiarizing themselves with the sounds. Buehler says that after listening to the resulting melodies, he is now able to distinguish certain amino acid sequences that correspond to proteins with specific structural functions. “That’s a beta sheet,” he might say, or “that’s an alpha helix.”

Learning the language of proteins

The whole concept, Buehler explains, is to get a better handle on understanding proteins and their vast array of variations. Proteins make up the structural material of skin, bone, and muscle, but are also enzymes, signaling chemicals, molecular switches, and a host of other functional materials that make up the machinery of all living things. But their structures, including the way they fold themselves into the shapes that often determine their functions, are exceedingly complicated. “They have their own language, and we don’t know how it works,” he says. “We don’t know what makes a silk protein a silk protein or what patterns reflect the functions found in an enzyme. We don’t know the code.”

By translating that language into a different form that humans are particularly well-attuned to, and that allows different aspects of the information to be encoded in different dimensions — pitch, volume, and duration — Buehler and his team hope to glean new insights into the relationships and differences between different families of proteins and their variations, and use this as a way of exploring the many possible tweaks and modifications of their structure and function. As with music, the structure of proteins is hierarchical, with different levels of structure at different scales of length or time.[…]

Source: Translating proteins into music, and back – ScienceBlog.com