A discovery made while designing an exhibition reveals surprising parallels with our current moment.

A discovery made while designing an exhibition reveals surprising parallels with our current moment.

Apr 1, 2021

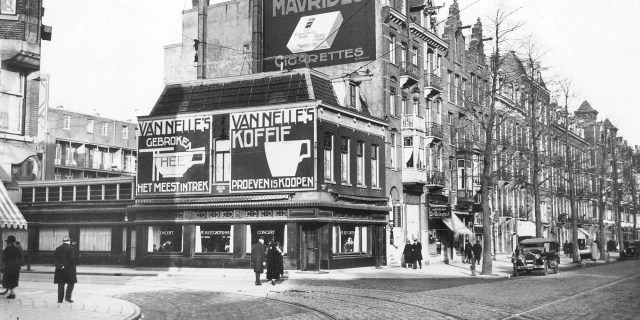

Behind the curves and corners of MoMA’s Engineer, Agitator, Constructor: The Artist Reinvented exhibition, mural-sized photographic wallpapers reveal themselves in moments of surprise. These wallpapers contextualize the early-20th-century works of art and design in the exhibition, offering glimpses of the past, inviting us to imagine what it was like to have lived in another place and time and—and to envision how the worlds within those photographs shaped the artists whose works are on view.

This aspect of the exhibition’s design started out as a small archival photograph, which I scanned to make 100 times or more its original size. All of the scratches and thumbprints become amplified and larger than life, interrupting the viewer’s entry into the image. I digitally retouch these blemishes, working inch by inch in a process that takes days of detailed work to create a more legible, more inviting reproduction.

While digitally cleaning pixels on several of the images we planned to reproduce for the exhibition walls, I found multiple instances of masks on the faces of sidewalk promenaders. I probably wouldn’t have given them much thought had I not been wearing a mask myself as I erased each tiny mark and looked at every spec of dust on the image. The connection of past and present was immediate. I alerted the curatorial team to the discovery, which led my collaborator Jane Cavalier to investigate the date of one photograph in particular.

–Claire Corey, Production Manager, Creative Team

To research art and design meant for streets, train stations, shop windows, and other public places in early-20th-century Europe and Russia, the curatorial team looked closely at public spaces themselves. We gathered historical images documenting how the posters, advertisements, magazines, and other works in the show were originally installed on city walls or in storefronts. Enlarged images in the exhibition provide context for visitors, revealing forces that shaped artists as they developed these works, from the speed of modern transportation, to urban bustle, to the dynamism of signage integrated with architecture, competing for attention.

When Claire discovered the masked figures in this photograph of Jacob (Jac.) Jongert’s advertisements for coffee and tea produced by the Dutch company Van Nelle, I immediately wondered if the image might stem from the early 1920s, amid a late wave of the 1918 influenza pandemic in Holland. Jongert lost his first wife to the outbreak in 1918, just a couple of years before he joined Van Nelle’s advertising department. By the late 1920s, Jongert had departed from the highly decorative Wendigen style, which was the major influence on Dutch graphic design at the time, to promote a functionalist approach that privileged clarity of communication. The advertisements we see on the wall of the building in this photograph reflect this later style in their playful yet concise typographic arrangements, use of highly legible sans serif letters, and high contrast, allowing us to date the photograph to ca. 1930. But this presented a dilemma: the Spanish flu subsided in the early 1920s, so why would people still be wearing masks almost a decade later?

In my research, I have found a number of images showing the persistence of mask-wearing as a preventative measure against the flu for decades following the 1918 pandemic. […]

More: The Museum of Modern Art

That pandemic killed about 140 millions of people world wide.

LikeLike

But sadly, two or three generations later was all but forgotten – hence our unpreparedness…

LikeLiked by 1 person